Andrew Stone, Oct 10, 2017

“A miner must extend the blockchain to communicate that it is too hard to extend the blockchain.”

The standard difficulty adjustment algorithm can be described as a black box D that accepts the blockchain as input and provides the difficulty of the next block as output.

D(N+1, Blockchain(0…N)) → value

We can measure the quality of different D algorithms by looking at their variance from the ideal algorithm that is provided the actual mining hash rate for the next mining period. Or by measuring the deviation of the resulting average block discovery interval from the 10 minute ideal.

Let me now prove that producing an algorithm that guarantees some minimum quality is impossible, given (game theoretic) profit maximizing miners.

The current price of the token is determined by external forces (it effectively is a random variable, or more accurately a chaotic variable since its value is better modeled using chaos theory mathematics), and it can change rapidly relative to blockchain updates. However its value determines whether blockchain updates happen, if we assume that miners are profit maximizing.

It is clearly possible for a sudden price drop to cause the system to enter into a state where the mining profitability becomes negative at a particular difficulty level, because in the extreme the price could fall to zero. More realistically, it is possible for a reasonable price drop in this coin and a reasonable price appreciation in another coin to make mining another coin more profitable than mining this one.

This will cause the profit maximizing miner to move all mining power to the profitable coin. Due to the nature of the mining problem, miners are not competing in the short term against each other — they are simply trying to create a block that exceeds a particular difficulty value. Therefore, having fewer miners mining a particular block has no effect on a miner’s profitability. The blockchain will never be extended. If the blockchain is not extended, no difficulty algorithm will can produce a different output.

In other words, no difficulty adjustment algorithm that relies solely on blockchain data can possibly have the knowledge needed to adjust difficulty in response to price changes.

This is the “blockchain difficulty information paradox”; a miner must extend the blockchain to communicate that it is too hard to extend the blockchain.

The EDA unfortunately doesn’t solve the problem. It uses the “MedianTimePast” algorithm to determine whether the EDA should occur. This algorithm returns the median time value of the last 11 blocks. The EDA compares the MTP of the chain tip with the MTP of the 6th youngest block and activates if that gap took 12 hours or more. So when price volatility causes blocks to become unprofitable at the current difficulty, a few unprofitable blocks must be mined at this difficulty level even after an EDA is “locked in”.

In the extreme, this could theoretically cause a “chain death” scenario, where no miner is willing to produce any blocks. There are a few possible reasons why “chain death” has not occurred even though the EDA does not solve the blockchain difficulty information paradox:

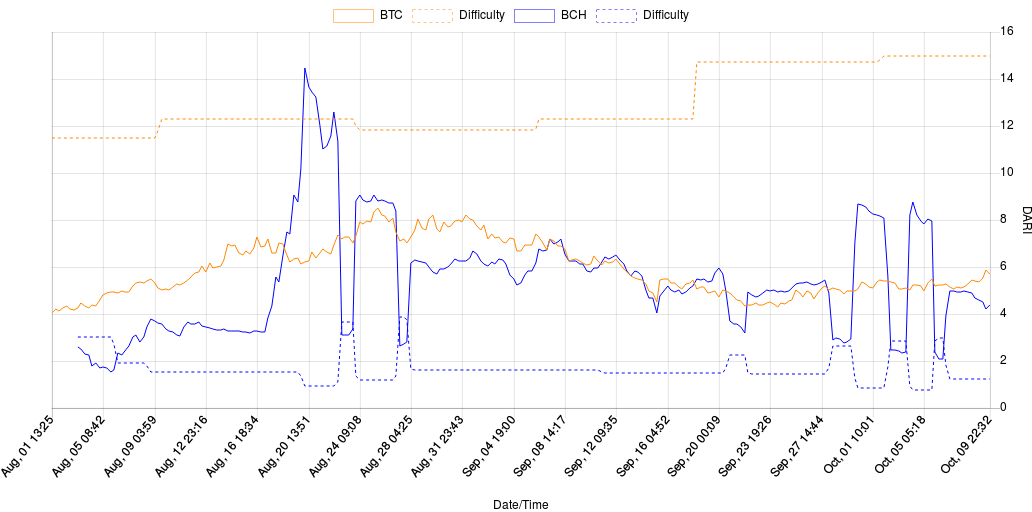

The following graph of mining and difficulty shows the above behaviors.

Credit: fork.lol

This graph shows benevolent miners keeping the block discovery rate above zero during the EDA periods. However, note that this “benevolent” rate seems to be decreasing, implying that these miners are tiring of the service. And note that the majority of miners are profit maximizing — as soon as the EDA happens, many miners start mining.

As the graph above clearly shows, unfortunately the EDA causes the difficulty to adjust discontinuously, and this discontinuity is reflected in block creation times — when its unprofitable to create blocks we get few or no Bitcoin Cash blocks, and when the EDA happens it suddenly becomes very profitable and so one difficulty adjustment worth of blocks are rapidly created.

We need to solve this problem by introducing a new source of data: calendar time (that is, time since a universally agreed upon beginning, rather than a local time interval). This breaks the blockchain difficulty information paradox because this time data is available continuously. A simple way to introduce calendar time is to make the time recorded in the current block relevant to the difficulty calculation. Yes, “uncooperative” miners could mine a block with a time stamp in the future, but the honest node majority will not relay or process that block until it “matures”.

This idea implicitly supposes that we can trust the aggregate opinions of the network’s nodes as to what the current time is. In other words, it IS possible for miners to collectively choose to lie about the current time, accept other miners’ lies about the current time and in doing so mine blocks and mint new coins extremely rapidly.

However, this is no worse than Bitcoin’s security model which also requires a majority of honest miners with reasonably accurate calendar time. Today, by advancing “block time” quickly relative to “calendar time”, a colluding majority of Bitcoin miners could cause difficulty reductions and ultimately mine all the reward-producing blocks early. But note that these blocks would be rejected by the rest of the network as being too far in the future, and from an economic perspective this collusion would be a disaster — the behavior would be quickly detectable by all participants in the network, and cause a loss of confidence in the new coin fork that miners effectively created by forking away from economically relevant nodes into a chain with very high inflation.

[Nov 2020 note: BCH’s consensus algorithm has made two changes called “finalization” and “parking” that depend on calendar time, so concerns about using this information source are less prevalent today]

Proposals to change the mining difficulty have been suggested by Deadalnix, Kyuupichan and Tom Zander. In my reading of these proposals, none use a extra-blockchain data source (please correct me if I’m wrong, proposals are written loosely in mailing-list conversations and I may not have read final versions). Therefore they are all subject to the blockchain mining information paradox and a “chain death” scenario is possible (as it is with Bitcoin by the way), in the absence of benevolent miners.

I believe introducing an extra-blockchain data source is important to ensure that the proposals do not ultimately rely on benevolent miners. I would recommend two avenues of research:

Use an algorithm very similar to the EDA or other current proposals, but introduce wall clock time as a data source, thereby allowing difficulty to change continuously in a downwards direction (as blocks are not found) and in steps upwards (when blocks are found early).

Use subchains (“weak blocks”) to communicate information between full block discovery. This breaks the paradox because there is an additional source of information not blocked by difficulty. Since only the weak block’s header is necessary to pass the relevant information, this information can be communicated and stored efficiently (a block can justify its difficulty reduction by including references to weak blocks that therefore also must be stored). However, there is some complexity here since one must incentivise miners to honestly publish discovered weak blocks, rather than (for example) withholding high difficulty weak blocks.

However, these two approaches still have tracking problems — notably a large price decline or increase will cause a period of no block creation or too many blocks respectively.

Actually, when we really think about it, Bitcoin’s algorithm has extremely variable block discovery times.

A New Approach

[Nov 2020 note: this approach favors large miners who withhold their block (and mine on top of it) until the interval has elapsed. Other approaches which reduce difficulty based on time are being considered]

I’m considering a new approach which certainly does have issues that need to be explored. And without help, I certainly will not drive this to completion soon so this approach should not really be seen as in competition with the other proposals if a hard fork is needed this year.

Let’s turn the standard mining algorithm inside out — instead of accepting the first block that meets a particular difficulty, let’s accept the highest difficulty block discovered within a particular time interval I. This introduces the time variable in an interesting way, therefore avoiding the blockchain difficulty information paradox, and causes miners to directly compete with each other for the next block. This direct competition means that as long as the token price is nonzero, a profitable block can be mined (with very low difficulty).

Formally, let us propose that:

Standard proof of work problem:

Hash(block) ≥ D

Block creation time constraint:

block.Tb — Parent.Tb <= I.

In the case of chain forks, honest nodes choose the chain with the most cumulative difficulty. If 2 chains have the exact same cumulative difficulty, the situation is similar to when simultaneous blocks are discovered on the Bitcoin blockchain — “random walk” analysis shows that one side of the fork will quickly pull ahead.

Let us analyze attack scenarios.

[ thoughts: If cumulative difficulty calculation is changed to reduce the value of parent block difficulty will this solve the problem?: For example:

CD(n+1) = BlockDifficulty(N+1) + CD(N)/2

The point is that the value of his high difficulty withheld block is reduced by half every block interval.

A high difficulty solution might still allow this miner to earn a few blocks in a row, but by attempting to mine a high difficulty solution, the miner reduced his chance of finding any solution at all. What is the optimum choice for D?

Is it OK for a miner to get an advantage on the next block, so long as that advantage is symmetric and not determinant? (in other words, who cares if a miner can produce a few blocks in a row so long as another miner has on average an equal chance at getting a turn to produce a few in a row)]

If the parent block is private, this is the block withholding attack described in 1. If the parent block is broadcast to the network, this is a valid strategy that can be employed by any miner and therefore gives no relative advantage.

This is analogous to the Bitcoin “sibling” block race today, except that in the Bitcoin blockchain, the race for the next block starts with both forks having the same difficulty. In our case, one fork is very likely to have a lower cumulative difficulty making this strategy less effective than in Bitcoin.

This is equivalent to mining a fork block at some past block height in the Bitcoin blockchain — useless unless you have a hashing power majority since the currently active fork will be longer, and tend to get longer faster than your fork.

However, this is a theoretical danger in all blockchains today. In theory, an extremely high transaction fee could cause all miners to stop mining children of the longest chain and start mining siblings (and then forks) of the block that reaped the fee in an attempt to get lucky and reap the high transaction fee. In practice, miners tend to benevolently return extremely high fee transactions to the person who accidentally created it.

Meni Rosenfeld’s proposal (2012):

This is an interesting post where Meni proposes to vary the reward and the block time, yet keep the reward to difficulty ratio constant. This will therefore not change the profitability of the block, and so does not solve our problem of block profitability and therefore hash rate volatility. However, it could be used to allow “benevolent” miners to produce more blocks. This benefit should not be dismissed — if Bitcoin Cash’s benevolent miners could keep block intervals consistently around 10 minutes even when most miners have left, our issues with the EDA would be much less critical since the BCC blockchain would still be meeting the most important task of committing transactions quickly and consistently:

Deadalnix’s proposal:

https://lists.linuxfoundation.org/pipermail/bitcoin-ml/2017-August/000136.html

Kyuupichan’s proposal:

https://lists.linuxfoundation.org/pipermail/bitcoin-ml/2017-October/000305.html